Title

On the Art of Exploring a City

Category

Reflection, urban perception, banalities

Type

Essay

Year

2025

On the Art of Exploring a City (2025) examines the relationship between the body, perception, and urban space through an autobiographical reflection on walking in the city. Using everyday movement through Berlin as a point of departure, it frames slow walking as a resistant practice that interrupts the logic of urban acceleration. Central to the text is the question of how pausing within the flow of the city can generate attention toward marginal, everyday phenomena. The narrative interweaves micro-level observations with an intergenerational memory, tracing the transformation of a child’s refusal to slow down into an adult’s reflective mode of perception. »Photographic seeing« is not treated as a technical act, but as a form of aesthetic and affective attention to the fleeting qualities of urban life. The text offers a theoretically informed, subjectively grounded perspective on urban perception practices situated between movement, memory, and visual thought.

↘︎ Download full text PDF (EN)

We move through streets every day, pressing forward with an urgency that feels self-imposed yet strangely absolute. Always moving, always navigating—hurrying from A to B as though the next place might finally offer relief. The city rewards this haste with noise and friction: the jostling bodies, the sharp edge of stress, the dull weight of exhaustion. In larger cities like Berlin, this rhythm becomes a way of life, a relentless pace that leaves little room for reflection. As we speed through urban canyons, dodging each other’s presence, we grow distant—not just from the streets and buildings around us, but from the selves we carry within.

I remember being ten years old, trailing my father during one of our family holidays. He had a habit of slowing down in places unfamiliar to us. »Walk slower,« he would say, »and you’ll notice the beauty of things.« I didn’t understand. I was restless, impatient to move on and see more. His advice, reasonable and true, sounded abstract, even ridiculous to a child eager to cram the world into fleeting moments. For years after, I kept rushing, though my reasons had shifted. It wasn’t curiosity anymore; it was something else—a compulsion to arrive, to finish, to move on. I was no longer seeing; I was merely passing through. It wasn’t until much later—at a random intersection in Berlin—that something in me faltered. Forced to stop by the red light and hemmed in by the flow of the city, I decided, almost without thinking, to take a breath. I looked around. A woman in a dress, its colors muted and graceful, stood across the street. Nearby, a man leaned against a corner shop, his entire outfit—down to the tablet in his hand—a study in lilac. A man walked two enormous dogs, their movements incongruously elegant. Smells drifted past: pizza, coffee, stale beer, cigarettes. The ordinary details of the street unfolded before me, not as obstacles but as offerings. The light changed, and I crossed, smiling faintly. What had just happened? Had the act of waiting, of doing nothing, opened some door?

As I continued walking, I noticed more: the interplay of shadow and light, the textures of walls, the angles where lines met unexpectedly. My father’s long- forgotten advice came back to me, and with it, a faint ache. He had stopped saying it after a while, perhaps resigned to my inability to understand. Yet here I was, two decades later, stumbling upon the truth of his words. The city, when you let it, teaches you how to see. The stroll, once a fixture of Sundays, has largely disappeared. It was, after all, a way of connecting—with family, with oneself, with the rhythm of a world that once seemingly moved slower. Writers, artists, and photographers knew this; their work often emerged from the quiet attentiveness of wandering. Henri Cartier-Bresson comes to mind, his lens drawn to fleeting, unposed moments. Yet in a time when slowness is met with suspicion, strolling has become an oddity. When people notice me walking slowly, phone in hand, they often stop and ask: What are you doing? Why here? Their questions, though tinged with unease, sometimes lead to warm exchanges. Occasionally, they lead to nothing. I’ve learned to welcome these moments. To pause at a red light is no longer just an act of compliance but an opportunity. The city, even in its most chaotic spaces, invites us to see. To slow down is to let the world seep in—to notice, to be changed by it. When I told my father about these small revelations, he smiled and said, »You see? That’s what I was trying to tell you all along.« His words stayed with me, quiet but insistent, like the light catching on glass at just the right angle.

There is something about moving too quickly that feels violent, even if the violence is subtle, it is a violence we inflict upon ourselves. In a place like Berlin, speed becomes second nature, an unspoken rule. The streets are structured for efficiency, not intimacy; their lines and flows seem to mock the idea of pausing. Yet within this relentless pace lies the tension of absence: the absence of the present, the absence of attention. We hurry forward, but toward what? Most of the time, we don’t even know. That day at the intersection felt like an interruption, but in retrospect, it was a gift. The waiting itself became a kind of seeing. Noticing the details—the lilac man, the woman in her dress, the mingling scents—was less about the objects themselves and more about the act of noticing. When I resumed my walk, the city unfolded differently. The way the sunlight hit a broken beer bottle and refracted into something momentarily beautiful. The way the cracks in the pavement formed patterns I had never thought to trace. These moments were small, fleeting, almost imperceptible, but they were also profound. I began to understand what my father had tried to teach me: that attention itself is a kind of love, and love—directed at the world, at the unnoticed—has the power to transform.

These days, I walk slowly, more slowly than most people find comfortable. My pace unsettles some; I see it in their sideways glances. When they stop to ask what I’m doing, I explain in as few words as possible. »I’m looking,« I say. Most don’t understand. A few do. Occasionally, these encounters lead to conversations or even a shared walk. More often, they lead to nothing. But that’s okay. I don’t walk to be understood; I walk to understand.

Image: Alexandre Kurek, Berlin Kreuzberg, Germany 2017.

The City

Reflection, urban perception, banalities

Essay

2021

The City (2021) conceptualizes the modern city not as a static built environment but as a living organism embedded in a continuous and reciprocal relationship with its inhabitants. The city is understood as a form of collective memory—absorbing, structuring, and reflecting the traces, narratives, and emotions of those who move through it. In this relational perspective, urban space is never neutral; it is shaped by social practices and sustained through both individual and shared imaginaries. The perception of the city fluctuates between poles of utopia and dystopia: it can appear as a space for self-realization and appropriation, or conversely, as a fragmented, alienating system. Urban experience is framed as a performative process in which identities, spatial configurations, and narrative structures are continuously co-produced. Responsibility for the city’s future lies in the present—specifically in the actions of its inhabitants, whose everyday practices continually influence the city's visual, social, and emotional fabric. The text articulates an ethical and political imperative to actively participate in shaping urban life and to acknowledge the city as a shared space of meaning, memory, and potential.

↘︎ Download full text PDF (EN)

The modern city, as we know it, is indeed a gigantic man-made structure, yet on a deeper level, it remains an organic one—a living and breathing creature, if you will; it either grows and flourishes, or it withers and dies, depending on how we, its inhabitants, nurture or neglect it.

I perceive the city as a living organism, a collector, telling the stories of its people—their history, achievements, ideology, and fears—always aspiring to have its own unique character whilst constantly demanding our attention. The city never forgets; it absorbs, internalizes, and reflects the behavior of each of us. Every single person that wanders in it—whether a visitor or a resident—leaves their footprints, little pieces of their personality, traces of their existence. We provide the substance that sustains it, and the city is a passionate gatherer. It truly loves our stories; around every corner, behind each façade and through every window, in every second of the day or the night, life unfolds in its purest form, and the city delightfully experiences all of it—yet remains a trustworthy listener and stays concealed, never revealing its secrets. You can expect it to keep your secrets—unless you want your stories to be told, in which case the city serves as a blank canvas, waiting for you to leave your mark. It almost dares you to claim even the smallest corner, to carve yourself into its ever-changing fabric. So go ahead—wander around and leave your marks for others to discover. The city will embrace your gift with gratitude.

For those who dare, the city can turn into a dream fulfilled—as they see it as something inspiring, emotional, and surprising—providing them with nearly limitless possibilities for self-expression and growth, allowing them to live a prosperous life. For those who don’t, the city might transform into a cold, indifferent labyrinth of concrete and glass, overwhelming them with its rationality, leaving them trapped in a suffocating, anxious existence. Though the city itself is never truly menacing but merely a mirror of our own inner selves—a reflection of our soul, if you will—it can strike us with the utmost severity at any given time if we feel threatened by it. The city needs to adapt to us as much as we need to adapt to our city. It yearns to become an integral part of our lives, and in the same way that we all are a vital part of what defines it, the city is inevitably a vital part of what defines us. We live in a close relationship with our city—a synthesis; we nurture and shape the city, and in return, it allows us to do the same. We—each and every individual roaming its streets—collectively shape our city, thus providing it with a unique visual identity and making it what it is today: whether a benevolent mother, in whose embrace we find safety, or a relentless, all-devouring behemoth.

We all bear responsibility for our actions, for it is our deeds today that will shape the city of tomorrow. It's up to us to make our city more diverse, more special, and therefore, more desirable; to define whether it is a blessing or a curse. It's up to us to create a city in which we all want to live. So let’s create—and always keep in mind: all cities are beautiful.

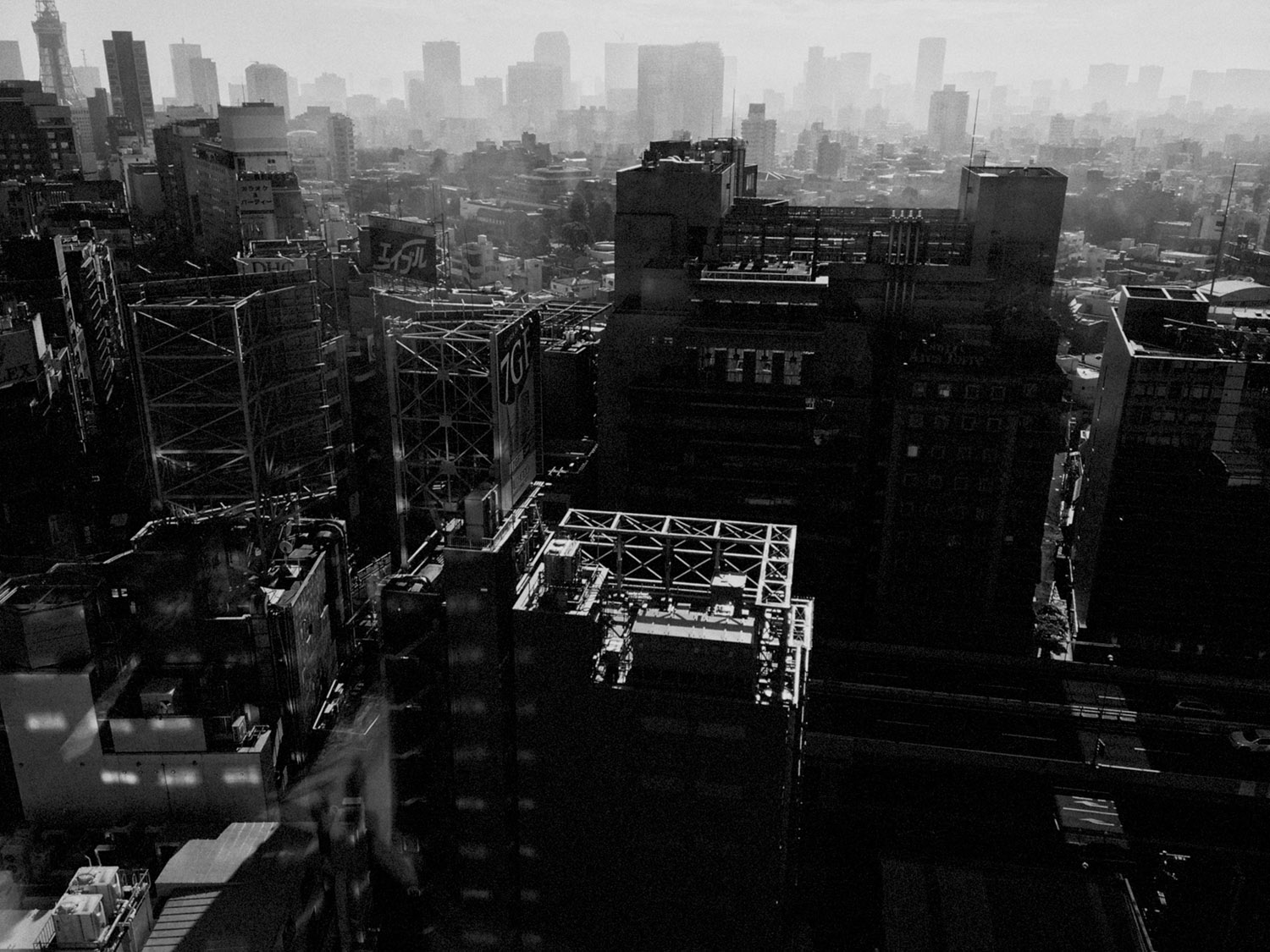

Image: Alexandre Kurek, View from Hotel, Tokyo, Japan 2020.

A Rainy Day in Marrakech

Reflection, urban perception, banalities

Essay

2021

A Rainy Day in Marrakech (2021) reflects on a moment in Marrakech (Morocco) that challenges dominant visual and narrative representations of the city shaped by tourism and media. Contrasting the usual imagery of vibrant markets and picturesque scenes, the account foregrounds a melancholic, rain-soaked urban atmosphere that reveals aspects of everyday life typically excluded from the tourist gaze. Through observational description and photographic reflection, the city is portrayed as a layered reality marked by absence, boredom, routine—and sudden tragedy. The narrative emphasizes the disparity between curated public images and the mundane, often invisible dimensions of urban experience. By resisting spectacular or exoticized framings, the text articulates a documentary and affective approach to urban photography focused on the unnoticed and the ordinary. In doing so, it formulates a critique of visual regimes shaped by commercial tourism and affirms the political relevance of attentiveness to the seemingly insignificant in the urban everyday.

↘︎ Download full text PDF (EN)

It was almost as if the rain had washed away any traces of an identity we—the tourists, travelers, photographers, writers—had given to Marrakech over the years, and had now revealed a much truer reflection of a city usually depicted as far more colorful and exciting than it truly is. But not on that day. Gone were the beautiful, rich colors and the smells of various spices and freshly cooked foods, typically experienced in Marrakech. Instead, I was witness to a grey and flavorless, almost melancholic truth of the so-called Red City—unveiling a deeper drama of mundane life right before me, capturing my deepest attention. Wandering through almost deserted streets, I caught a glimpse of a reality hidden from most of the foreign visitors—a reality filled with boredom and futility. There was no need for artificial excitement, for there were simply no tourists present who had to be artificially kept excited. The only people present, aside from a few stray visitors like myself, were Moroccans going about their business or seeking shelter from the rain under canopies, in shops, or doorways, minding their own lives.

I met Nick at Café de France later that day. After being separated for a few hours—we decided to go our separate ways for a while to focus on taking photographs without distracting each other—we sat down to have a coffee and talk on the roofed balcony, just minutes before a heavy rainstorm hit. As those seated in the front row of the balcony fled from the fierce rain, Nick and I—seated safely in the back row—were rewarded with an excellent view of the usually crowded Jemaa El Fna square. We watched in awe as the storm grew stronger, with lightning strikes illuminating the sky, while people across the square frantically ran, seeking shelter. The sky cleared, and the storm ended just as abruptly as it had started, as we continued our journey through Marrakech together. Drawn to a crowd of people gathered in front of a large but inconspicuous building next to the Maison de la Photographie—which we had just visited—we decided to stay and observe the scene for a little while. It quickly became clear that the building was, in fact, an elementary school about to end its classes, and soon the people in front of it were greeted by dozens of children rushing out, screaming, chanting, and laughing—young lives invigorating the lifeless streets once again.

Stepping back to an opposite wall while joyfully watching the children embrace their loving parents, I looked around and noticed five or six men approaching quickly, carrying a gurney loaded with something unidentifiable, covered only by a white sheet. Seemingly unnoticed by the parents—too caught up in the excitement—the men slowed down, shouting as they pushed their way through the crowd. Catching a glimpse of what lay hidden beneath the sheet, I realized they were carrying the dead body of a young boy, carrying him as fast as they could through the narrow streets of Marrakech to whatever their final destination was. A man standing next to me—one of the very few who had noticed the scene—quietly told me in French that he had heard about the recent tragedy of a young boy struck by a speeding car, not far from the very school where he and other parents had been standing, eagerly awaiting their children. »Il est mort,« he said in a subdued voice, certain of the boy’s fate. »They're rushing him to a nearby hospital, but it's already too late. He's dead. It happens a lot around here. People get hit by cars almost every day. It's horrible. You just can't be careful enough,« he continued, shortly before embracing his own son and disappearing around the corner, his hand tightly pressed around his son's.

Pictures of Marrakech—and Morocco in general—often show us only the sunny days, the vibrant markets, the delicious food, the carefully curated tourist attractions in the Medina, the architecture, smiling elderly people, cats, and donkeys, and all manner of colorful, playful scenes, as captured in some of my other images. But a beautiful color palette doesn’t matter if there is no light illuminate it. I guess, in a way, that was the reason why I chose to photograph mostly in black and white that day—so Marrakech, the Red City, could remain grey and sunless for a day, mourning the loss of yet another son.

»We like to pretend that what is public is what the real world is all about,« as Saul Leiter once said. But the truth is, there is always another world hidden beneath what is obvious and purposely displayed—a world not often photographed or recreated countless times before due to its mundane and unspectacular nature. But it is not sensationalism that drives me or that I seek in my photographs. It is the ordinary lives of ordinary people that interest me. On that day—while aimlessly roaming through Marrakech at first—I somehow managed to catch a glimpse of the very reality I seek, and I am deeply grateful to have experienced it.

Image: Alexandre Kurek, Marrakech, Morocco 2016.

Between Weight and Gesture

Reflection, media practice, visual culture

Essay

2020

Between Weight and Gesture reflects (2020) on the shift from conventional camera use to smartphone photography. Based on a personal experience while traveling in Morocco, it shows how the smartphone, as a photographic medium, alters not only the act of taking pictures but also perception and social dynamics in public space. Central to the text is the question of how technology shapes not only the production of images but also visibility, access, and agency within urban contexts. The essay contributes to a media-theoretical perspective grounded in everyday practices, where photographic gestures structure relationships as much as they document them. It is based on a reflection following the journey through Morocco and a related interview with Anne Schellhase, published in fotoMagazin (2017).

↘︎ Download full text PDF (EN, DE)

Why did I start taking photos with my phone? The most honest—and at the same time the most imprecise—answer would be: out of laziness. Although this term—too often morally overloaded—points less to inertia than to a form of pragmatic efficiency, to a desire to detach the photographic act from the weight of technical apparatus, from their symbolism and visibility.

For a long time, this weight was part of my practice, of my posture (in the figurative and literal sense). Anyone travelling with a camera, lenses, film rolls, memory cards and a hard drive does not engage in casual image-making but marks themselves—for others as well as for themselves—as someone who means what they do. This kind of visibility, through which the photographer inscribes themselves into public space, was not unpleasant to me; it lent a certain gravity to being on the move, a self-imposed obligation to pay attention. And yet, this relationship began to shift during a journey through Morocco—not abruptly, but casually, almost as a side effect. It was a moment during the ride from the airport in Fès into the medina when, for the first time, I didn’t reach for the camera but pulled out the smartphone from my jacket pocket. The setting sun above flat rooftops, the unfolding relief of the Atlas Mountains, people at the roadside—fleeting impressions I recorded without positioning myself. Not prepared, not in photographer mode, just simply: there. Photographing became a reaction to what was seen, not a staging or framing of it. When I looked through the images later, I was surprised by how much they retained: not just subjects, but a rhythm, a movement, a relation to the situation.

In the days that followed, I first left the camera in the backpack, then in the room. I continued to photograph—frequently, attentively, but inconspicuously. What changed was not just the device, but the relation to space. People responded to me differently. I was no longer marked as a photographer—not as a potential intruder, chronicler or observer, but simply as a person present. It became easier to make contact or to remain unnoticed. The phone, already ubiquitous, doesn’t attract attention—it evades it. The gesture of photographing with a phone is less an action than a movement, embedded in the flow of everyday life. This brought a question to the foreground, one that goes beyond technical or aesthetic considerations: To what extent does the medium with which we photograph shape not only the image, but also our position in the social realm—our relation to the environment, to visibility? With the phone, I was able to move more freely through urban space, to cross thresholds without being perceived as someone who wants something. The camera signals intention; the phone allows a relation of observation without intervention.

From Fès to Marrakesh to Essaouira, through alleyways, squares, souks and harbours, this experience continued. I observed, recorded, responded—not from the distance of a technical device, but from the proximity of a light, inconspicuous gesture. It wasn’t about devaluing the camera or celebrating the smartphone, but about the question of how media practices inscribe themselves into social practices. Taking photos with the phone became a form of movement, a method of perception—and a technique that does not operate through technical superiority, but through situational adaptation. I haven’t stopped working with the camera. It remains part of my professional and artistic repertoire. But what I found unintentionally was a solution to a familiar problem: How can photographic work happen in a way that doesn’t stand out through technology, but functions through attentiveness? Perhaps this marks a small shift: away from the image as object, towards photography as relation.

Image: Anja Rausch, Berlin, Germany 2025.

Back to top